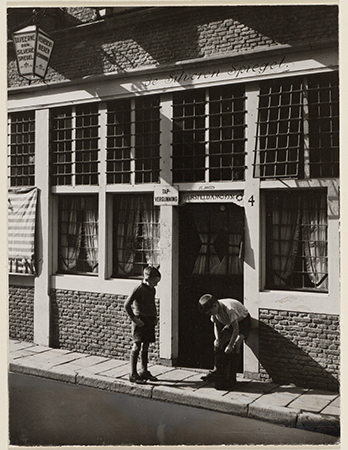

1614

KATTENGAT

The Golden Mirror and the Silver Mirror

The quaint and often very expressive names are part of the magic of the old town. The Kattengat or Cat-hole is said to owe its name to the fact that it was once a ditch connecting two moats that was so narrow that not even a cat could get through. There were four of these narrowing in mediaeval Amsterdam.

Strategic Importance of Waterways

The Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal and Nieuwezijds Achterburgwal were connected at the north end by the Kattengat and by a second narrowing at the south end where the Spui now meets the Singel. A similar situation obtained at the other side of the town where the Oudezijds Voorburgwal and the Oudezijds Achterburgwal were connected by ditches at Oudezijds Kolk (a kolk is a chamber of a sluice) at the north and Grimburgwal at the south end. These narrow cuts were obviously of strategic importance in a town where water traffic played such a vital role.

Transformation of Kattengat

The Kattengat was filled in 1601, remaining a narrow alley until 1936. Since the inauguration of the Round Lutheran Church in 1671, its green brass dome has dominated the townscape with its colour and bulk. Many prominent citizens are buried in the church. The twin step-gabled houses at 4 and 6 Kattengat were built in 1614 for the wealthy soap-boiler and town councillor Laurens Janz. Spieghel.No 6 was called De Goude Spiegel, the golden mirror, and no. 4 De Silveren Spiegel, the silver mirror.

Architectural Details and Craftsmanship

The sandstone finials are formed by four mirrors each. A cartouche bears the date 1614. Spieghel seems to have relished the pun on his name for he called his own residence De Drie Spiegels, the Three Mirrors. Like many early Amsterdam houses, both of these are supported by a wooden framework which has undergone some structural changes, however.

We may safely assume that the resilient quality of these wooden frameworks has saved many of our older houses from being shaken to ruin by the heavy axle-weight traffic of our day. Small as they are, these typically 17th-century houses embody the virtues of impeccable Amsterdam craftsmanship.

This is manifest in many details: the sturdy timbered basements, the small red bricks, solid wrought-iron cramps, sandstone bands and moldings, and the sandstone finials. Both houses originally had a front hall furnished with a spiral staircase. Since the property represented an investment, we can assume that the upper and lower floors were let as separate tenements; witch is suggested indeed by the position of the stairs immediately behind the front door.

Restoration by the Hendrick de Keyser Society

The Hendrick de Keyser Society who is concerned with the preservation of art-historically important buildings acquired both houses in 1926 and entrusted the restoration to A.A.Kok in 1932.

1940 1945

Restaurant de Silveren Spiegel during the WWII

Above the Mirror, Kattengat, Amsterdam

Barend de Hond just stands there on the Jonas Daniël Meyer Square, hands in the air, in the middle of a razzia. He works for a demolition company and is a sturdy man, not unlike the dock workers, who will go on strike later in protest of the mad persecution of the Jews. He knows a few words of German, enough to venture something. They are not going to get him; ‘Ich bin krangk. Pein in me ruck!’ he says in broken German (“I am ill, I have a backache”). It is his rescue, since the German allows him to leave. It is spring 1941, the German occupation of the Netherlands has become systemized and has become very unpleasant.

Finding Refuge at de Silveren Spiegel

De Hond understands the situation and goes home, knowing that he, his wife and his son cannot stay there for much longer. For his demolition company he has regularly worked near the Kattengat, and in the vicinity of the central station. He has often eaten a sandwich in the café beside the Lutheran church, de Silveren Spiegel. He knows the owner well. Wies Hofmann, an Austrian from Linz, who thoroughly hates her compatriot Adolf Hitler. Perfect for a Jewish family in search of protection. With his wife and only zoon Ab de Hond leave their home in the Swammerdamstraat and move to de Silveren Spiegel, where they will stay for the next four years. They hide under the ridge of the 17th century roof.

Ingenious Hiding Places

As a demolisher de Hond knows about all the nooks and crannies in the architecture of the Amsterdam Golden Age. He gets to work and creates an ingenious system of hiding places and panels to cover them up.

Hofmann’s café has been a popular haunt of German soldiers ever since the beginning of the occupation. Wies serves them schnapps with a broad German accent. She is quite fond of a drink herself, and acts her role in a flamboyant fashion. She knows her German customers well and none of these soldiers could ever suspect that Jews are hiding above their regular drinking hole. Oddly enough, their presence gives the hidden family an, albeit frail, sense of security. Nevertheless, they have to take care at all times and especially the drinking habits of Wies are a risk. She often gets so plastered that she forgets to close the door after the guests leave. Then Barend has to sneak down quietly, lock the door and hoist his protector into bed.

Life in Hiding

The de Hond family don’t remain with just the three of them, they are joined by more family members until sixteen of them hide under the roof. Sitting packed together like this is not very beneficial to the family relations, they often argue and bicker, but always keep it indoors. They kill the time playing cards, doing veneer work and forging stamps with Indonesian ink for the resistance. They are not entirely cut off from the outside world, because they can listen to the BBC broadcasts on a little radio.

Ab de Hond’s Perspective

From behind a small window with stained glass Ab often looks into the street, where he can see the Germans marching in their black uniforms.

By day, when the café is closed and the shutters are closed, he can come down to do little jobs in the bar, such as removing the fly droppings from the chandeliers. He also becomes quite skilled in installing barrels of beer. Across the street, on the Hekelveld, is the building of Het Volk, a pro-German newspaper. The janitor is called Landkroon. He has two daughters. They are good people and know about the people hiding in de Silveren Spiegel. Sometimes Greetje Landkroon comes up to give Ab school lessons. He reads a lot; children’s books, comics and about the adventures of Rudolf the knight. It does impair his eye sight. He is not the kind of boy to keep a diary like Anne Frank is doing not too far away on the Prinsengracht. Ab will only hear of her after they war, when she has already been destroyed.

Tragic Losses and Close Calls

In their uncomfortable hiding place, the family bereaves one of its members; Judith Walvisch. She gets a neck infection and there is no medication. She dies of blood poisoning. In the middle of the night her body is dragged into the street and left there, on the cobbles of the Singel, in the pouring rain. The police officers that find her are surprised that the soles of her shoes are still dry.

Life in hiding continues with dread, with sweat and with constant alertness, all the time suppressing the fear of being caught. From time to time shouting could be heard from the Kattengat; “Barend de Hond!” It comes from Meerlant, the neighbour of de Silveren Spiegel, who runs a removal company and has two daughters who both date German soldiers. Ab is still convinced that it must have been Meerlant who betrayed the de Hond family. The Sicherheitspolizei raids de Silveren Spiegel six times, but every time Wies Hofman manages to press an alarm button under the bar. Every time the Germans come no further than the attic, which they think to be the top space of the building. Then the stamping of the boots, the harsh voices and the sound of the straps of guns disappear again.

Nevertheless, German soldiers keep frequenting the bar. In the cul de sac between de Silveren Spiegel and the Lutheran church they sometimes park their army truck, loaded with goods, among which often food, such as very tasty canned sausages. Barend de Hond quietly sneaks down, climbs into the back of the car and steals the extra nourishment he can get. From the car he hears the Germans’ drunken brawls in the bar. Don’t ask how, but once he even manages to bring up half a horse.

It goes on and on. Days of duress cluster into weeks, months, years, the terrible wartime doesn’t seem to end. The exhaustive wait aches. But in the same time, life in hiding becomes a daily routine. It comes as a big relief when finally an alternative hiding place is found for some members of the family, after which only eight sit together in de Silveren Spiegel on the Kattengat, until the liberation. They were never put on transport, they never saw the camps. They have no stories of Westerbork, Auschwitz, Sobibor, or Maathausen.

Liberation and Life After the War

When, on May 5th 1945, for the first time in four years Ab steps outside, he is ecstatic and in a phenomenal explosion of relief he starts running, away from the attic, away from the round tower of the church next to it, away from the Kattengat, towards the station, towards the water. He runs and runs and runs, with all the energy freedom can give, inhaling breath after breath of the free fresh air. He stops at the Haarlemmerpoort and walks back to de Silveren Spiegel, a little more calmly, but still immensely happy, so very liberated from his lifesaving imprisonment above the beer draught.

When the Canadians arrive he climbs on one of the amphibian cars. It is quite an experience to be cheered, and then he drives together with those impressive men straight into the water of the IJ! Ab doesn’t fail to tell about the two daughters of Meerlant. As of so many girls who have slept with the Nazis, their heads are shaved bald.

For a while the de Hond family keeps living in the attic until they are given a new house on the Nieuwe Herengracht. After the war Barend de Hond picks up his old job as a demolisher and he also works for fellow Dutchmen who keep making anti-Semitic remarks, but once he overheard one of those characters say that he was ‘fed up with those cholera Jews,’ so naturally Barend hit that bastard, chair and all, across the tram rails of the Rembrandt Square. In consequence he had to appear in court, where the judge had the cheek to say that he did not want to see him back again for those kinds of incidents! Live is not easy for Jews, even after the war.

Mother dies in 1948 of breast cancer. Her son thinks it must have been the stress. Wies Hofmann doesn’t survive the war much longer either. The drink kills her. But her bar becomes the haunt of a new generation of journalists of the workers paper HET VRIJE VOLK en the VRIJ NEDERLAND, which was previously press of the resistance. But now that has passed, since both the papers have moved to the Raamgracht.

Ab de Hond first works on boats and on the de Johan van Oldenbarnevelt he crosses the oceans of the world. Back on shore in 1960 he becomes the owner of a radio shops in the Roeterstraat, and starts importing and exporting musical instruments. He retires in 1988, as a widower and father of three children. Music, percussion, remains his passion. He loves to drum Latin American style.

He still loathes the sound of boots and because it was the colour of those marching hounds, he wasn’t able to put on black trousers until the year 2000.

De Silveren Spiegel became a classy Old Dutch restaurant.

As the family has been well hidden for a long time, so has their story.

Translation by Patrick Faas

From

Oorlogspad (war path)

De bezitting voorbij (Beyond the occupation)

Wat Nederland nog over 40-45 vertelt. (What the Netherlands still tell about 40-45)

Author Jeroen Wielaert

ISBN 90-215-4189-0